When did you stop beating your wife, Dr. Mohler? That’s what is known as a loaded question, because it presupposes the truth of a controversial or unjustified assumption. Dr. Mohler, in his 1-25-17 Briefing, responded to an article by Moira Weigel published the previous day in The Atlantic titled “How Ultrasound Became Political”. Dr. Mohler said,

“Referring to the legislation requiring an ultrasound before an abortion, Weigel wrote, ‘These measures raise even more elementary questions: What is a fetal heartbeat? And why does it matter?’Now let’s just pause for a moment before going even a second further and recognize she’s actually asked the question, why would the fact that the baby has a heartbeat even matter? What matters is that she dares even to ask the question!”

But notice something that Dr. Mohler evidently didn’t: Weigel did not ask why the fact that a baby has a heartbeat matters. She asked why a fetal heartbeat matters. Mohler loads the question with the presumption, which is the very issue in dispute, that a fetus is a baby. He doesn’t argue for it. He never even questions it. Here it is again, in his account of “the moral background” of Roe v. Wade:

“If indeed the baby in the womb is a person, if that baby is a human life, then it must be protected rather than destroyed and effectively abortion would be what it is, a form of homicide.”

He seems incapable of even framing the question without assuming its answer: what’s in the womb is a baby and therefore obviously a person and a human life. That unquestioned assumption is part of his worldview.

Dr. Mohler’s specialty is worldviews, those packets of often unconscious assumptions through which we see the world. He speaks of them constantly. He believes they are the key to understanding the conflicts in our culture, and I agree with him. He is a proponent of what he calls “the Christian worldview.” (Whatever Dr. Mohler happens to believe seems to qualify.) “The Briefing” is even introduced as “a daily analysis of news and events from a Christian worldview.” In this Briefing he asked us to “consider the worldview” behind Weigel’s article. But he seems blind to his own. In fact, he believes that, in the case of the unborn, we can see what they are without relying on any assumptions at all:

“It turns out that seeing the baby inside the womb, even at very early stages of development, instinctively informs the person seeing the image that this is not merely a potential life, this is life. This is not just a potential person, it is a person. This isn’t just a maybe baby, this is a baby.”

Weigel’s article was in many ways a terrible article. She didn’t get her facts right – medical or political – necessitating multiple error corrections by The Atlantic and provoking a firestorm of tweets and comments. And she never explained clearly just what the alternative views a person might have of the unborn are, or why one view might be better or worse than another. But what I take to be the central point of her article was valid: an image on a screen does not determine what it means – what conclusions should be drawn from it. An image does not stand alone; what it means to us depends on what we bring to it, our assumptions about it and about the world. There are alternative conclusions one can come to about the unborn, even given an image resembling an infant in a sonogram or the sound of a heartbeat. We may have instincts or intuitions about what we see and hear that draw us to one conclusion, but we also have the capacity to reason. We can pause and reflect critically on what is shown and what is not shown, and take into account what we know from scientific investigation, and then weigh the evidence. That is the only reliable path to truth (short of divine revelation).

Do you ever peer into a baby carriage and say, “What a pretty adult!”? When you see a toddler taking its first steps, do you say, “What a strong teenager!”? If you see a child stumble, do you ever say, “That man is about to fall”? I don’t think so. So when talking about a human zygote (a fertilized egg), an embryo or a fetus, why do pro-lifers like Dr. Mohler always say “baby”?

Sean Davis, in a Federalist article Dr. Mohler referenced in The Briefing, said, “No amount of euphemisms can obscure the truth that unborn babies are alive.” But ‘zygote’, ‘embryo’, ‘fetus’ are not euphemisms. They are not attempts to avoid naming the reality. They are specific names for specific stages of human development. It is pro-lifers who have adopted a policy of avoiding use of the most accurate terms. In their place they’ve opted to substitute the name for a familiar thing we all have automatic emotional responses to.

The word ‘baby’ immediately evokes all the experiences we’ve had with bawling or smiling or babbling infants. We know what they are – we know all kinds of things about them – and we know how we feel about them, because they are familiar to us. But very few people are familiar from personal experience with zygotes or embryos or fetuses. We may have imagined them hidden away in a woman’s body, but we have not seen them in person. We have not interacted with them. We don’t know from personal experience what they’re like. So we don’t have the ready-made, rich emotional response to the words ‘zygote’, ‘embryo’, ‘fetus’, that we do to the word ‘baby’. And if we did have a rich variety of personal experiences with these beings, the chances are that we would not feel toward them as we do toward babies, because they are so unlike the babies we have known. They are only babies in the sense that, given time and nurturance, they could become babies. That is, they are babies in the same sense that babies are adults.

There is no doubt this pro-life tactic is effective. The emotional power of the accusation “baby killer” has a long and ugly history. Slanderous antisemitic stories of Jews ritually killing Christian children have led to murderous rampages. Fabricated stories of soldiers bayoneting infants or, more recently, throwing them out of incubators (in Kuwait), have been used to fuel wars. So if the goal is to win by firing up your side to fight a jihad against evil-doers, crying “baby killer” works. It inspires and motivates people, especially young people, who are ready for a moral crusade. But it succeeds by stopping thought:

We know we are against killing babies, but what about zygotes and embryos and fetuses at different stages of development? If we think about these unfamiliar entities specifically, we may find we are unsure. If they are the same as babies, then we can know that we are against killing them too; our path is clear. But in some ways they are the same and in some ways different. Are any of these differences morally significant? This should take some thought, which must start by distinguishing these different kinds of entities. But if you simply say, not that they are like babies in certain respects, but that they ARE babies – always using the same word for all of them – then you cannot even start the job, and you cannot make sense of someone saying, “Look here, first impressions of an ultrasound image of a 6-weeks embryo – an unfamiliar entity – may not be completely reliable. What is it really that we are seeing? What are we to think of it? How much moral consideration does it deserve?” To that you can only protest, with Dr. Mohler, “How dare she even ask such a question about a baby!”

Unfortunately, most pro-choice advocates, like Moira Weigel, aren’t any better at basing their judgments on careful consideration of what’s really there. They’ve devoted most of their energy to defending the freedom to choose, while leaving moral justification of the choice to have an abortion to one side, presumably as a matter of personal opinion. By not facing up to this question boldly (with the exception of a few philosophers) they have guaranteed the survival of the conflict, because they have not explained why abortion, in their view, is not immoral. Weigel seems to have only a vague conception of the embryo/fetus as a collection of cells; she calls it a “rapidly dividing cell mass”, implying that as such it is not worthy of moral consideration without actually arguing the case. Clearly she had made no effort to educate herself on the process of development, even of the organ (the heart) which she was writing about. This is shameful, and only harms her cause.

Let’s consider the heart. According to an online Embryology textbook, “In human embryos the heart begins to beat at about 22-23 days, with blood flow beginning in the 4th week. The heart is therefore one of the earliest differentiating and functioning organs.” Let’s dare to ask the question that Dr. Mohler was too outraged to address: why should it matter, morally, whether or not an embryo or fetus has a functioning heart? I don’t believe it does matter, to Dr. Mohler or to pro-lifers in general. That is, none of them believe it makes a moral difference. Dr. Mohler, after all, opposes use of the morning-after pill and other forms of contraception as possible abortifacients (with little basis in fact). For him the fertilized egg is already “a life, a person, a baby”, and it consists of a single cell. It does not need a heart to qualify as a human being in the full moral sense, according to pro-life ideology. The law in question, “The Heartbeat Protection Act”, which would make abortion illegal once a heartbeat can be detected, has no logic behind it except the fact that it is one more step toward total prohibition of abortion – that, and the convenient feature that the thought of “a beating heart” is emotionally evocative.

Let’s take that up briefly. What is the heart? The one in our chests is a pump. It circulates the blood. But there is another one, a mythical organ, which lives in many expressions in our language and is a favorite especially among some evangelical Christians. (President George W. Bush was among them.) We know things in our hearts. We hold things in our hearts. Our hearts go out to loved ones. Our hearts ache and break. We give our hearts. I’m not saying these statements aren’t meaningful or true. They convey important messages. But they are not about the organ that pumps our blood. They are about some conception of it – the heart as the seat of the emotions and of emotional knowledge – which does not happen to correspond to the actual physical organ.

Our bodies, including our hearts, do participate in our emotions – that’s how lie detectors work. But the core, necessary, essential organ of all consciousness, including thought, sensations, feelings and emotions, is a different organ: the brain. When you cut your finger, you feel the pain as if it is in the finger, but that sensation is taking place in your brain, or at least it corresponds most closely to events in your brain. That is why, if the nerves from finger to brain are severed, a cut won’t hurt because information about the injury never reaches your brain, and if you lose the finger, you may still feel pain in a “phantom” finger if the brain areas representing that finger and pain in it are active, even though the physical finger no longer exists. You may feel pain in your chest and call it heart ache, or warmth and call it love, but those sensations and emotions are taking place in your brain, though the heart probably participates in giving rise to them. And while the heart is one of the first organs to begin functioning during development, the brain is one of the last. So to the extent we think that the capacity to feel emotion or pain is morally significant, this should only affect the admissibility of late term abortions, since the brain is not capable of supporting them earlier.

But more than sensations, emotions and thoughts – our very sense of self, which is the core of our being – relies on a functioning brain. For me, that single fact – that without our brains we are nothing, we don’t exist – settles the question of the morality of 97% of abortions, namely those performed in the first two trimesters of pregnancy. (It is a fact according to my worldview, though not according to the Christian one.)

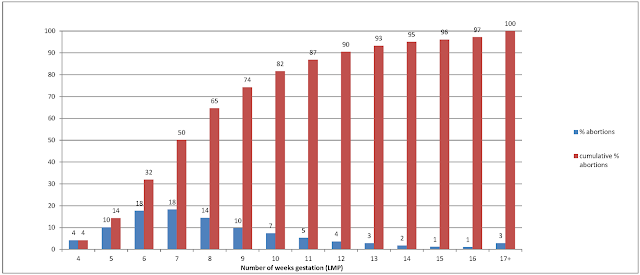

If you were to allow that what is actually there, in detail, might matter morally – that an early embryo might be a very different kind of being from a late stage fetus – then it would be important to know at what stage in pregnancy most abortions are being performed. According to a new study, based on a pencil-and-paper survey of over 8000 non-hospital abortion patients, these are the percentages of abortions performed during each week of gestation, and the cumulative percentages:

Note that “weeks of gestation” is measured from the first day of the last menstrual period, which means that the actual age of the embryo from fertilization is about two weeks less than the week number listed. The most frequent weeks are 6 and 7, very early in pregnancy (4 and 5 weeks since fertilization). 50% are performed by the end of week 7, two thirds by week 8, three quarters by week 9, 93% in the first trimester, and 97% within the first 4 months of pregnancy. The study found that need for financial assistance, a distant abortion facility and laws requiring a waiting period all resulted in later abortions. Fully 40% of patients in states with no waiting period had an abortion at 6 weeks gestation, but only 25% in states with waiting periods. (Guttmacher news release about the study.)

|

| Embryo 4 weeks post-fertilization |

At 6 weeks gestation, 4 weeks post-fertilization, the embryo is about the size of a lentil – 4 to 6 mm (a penny is 19 mm across)-- and does not look like any baby or any human you’ve ever seen. It doesn’t have a face but it does have a tail. Its proto-brain is a bent hollow tube sporting fluid-filled swellings called vesicles which will later develop into the major brain regions. It has a beating heart. Does viewing these images “instinctively inform you” that this is a baby and a person? Would you risk your welfare and that of your family in order to save its life? Is that an outrageous question to ask?

The absolutist pro-life ideology which views abortion at any stage of pregnancy as murder uses images of late-term abortions as symbolic of all abortions, although they are very unrepresentative. It never even considers the very great differences between embryos and fetuses at different stages of development. But many Americans (I don’t know the proportion, but I believe it’s a majority) are more troubled by abortions the later they occur. So laws which, as a result of an absolutist pro-life ideology, seek to delay abortions are actually, in the view of many Americans, making things morally worse.

Dr. Mohler throughout the podcast refers to the unborn as “a life”, “a person”, “a baby”, as if these were all equivalent terms. I have argued that “baby” is not an accurate description of early stages of human development, and is indeed a misleading one. Let’s finish up with ‘person’ and then consider ‘life’.

When I said the core of our being, our sense of self, relies on our brain, I was referring to personhood. One interpretation of our being made in God’s image is that we resemble God in this respect – that we are persons, like Him. God (in Western religions) does not have a body, but He does have a mind, a personal mind: he knows, he loves, he intends and plans, he enters into personal relationships. This is what being a person means. We too have minds which are personal. But human minds, in this world at least, are reliant on brains for their functioning, and arguably for their very existence. So it makes sense that what Christians refer to as the image of God would not be imprinted on our bodies until our brains became capable of supporting a personal mind. Only then would we become persons – human beings in the full sense. It’s a thought, anyway – though one advanced by an atheist. (For non-believers like me, only minds and minded bodies are of moral concern, never mindless bodies, which I take embryos and early fetuses to be.) But historically Christians have also held the view – under the label “delayed hominization” – that early stages of development were not fully human. (This has nothing to do with species membership, but with presence or absence of a fully human, ‘rational’ soul. The earliest soul of the embryo was thought to be plant-like, 'vegetative', which was then replaced by an animal 'sensitive' soul, and finally by the fully human one. Aristotle, the first embryologist, invented that.)

If the brain, more than any organ in the body, makes us who we are, and if a functioning brain is necessary for personhood, then this has consequences for how we are to interpret images of the unborn. Even when their external appearance becomes very baby-like, what counts morally is hidden from view inside the head. If you could see through the skull you would find that there is nothing baby-like about an unborn's brain until very late in pregnancy. Only then do the familiar walnut-like corrugations of the brain's surface appear, a symptom of the brain being connected up, the neocortex growing and folding within the skull, until it assumes that uniquely human appearance.

With mention of the soul, I’ve just now broached the subject of Dr. Mohler’s third honorific descriptor of the unborn: “a human life”. This is a complicated subject, in part because the word “life” has many meanings, which are often confused. (Dr. Mohler found it scary that Weigel put ‘life’ in what he called “scare quotes” “as if it were a term of art.” But ‘life’ does have many different meanings, and its ambiguities have been exploited by the pro-life movement.)

With mention of the soul, I’ve just now broached the subject of Dr. Mohler’s third honorific descriptor of the unborn: “a human life”. This is a complicated subject, in part because the word “life” has many meanings, which are often confused. (Dr. Mohler found it scary that Weigel put ‘life’ in what he called “scare quotes” “as if it were a term of art.” But ‘life’ does have many different meanings, and its ambiguities have been exploited by the pro-life movement.)

Consider three different meanings of ‘life’: narrative life, biological life, and animating life:

Biographies often have titles like John Smith: A Life. A biography is a narrative, a story, relating the series of events that compose a person’s life. So a life in the narrative sense can be the story, or the events the story is about. “He had a long life, an eventful life, a tragic life. His life was cut short. If you value your life.... You have but one life to live.” These are all narrative ‘life’. When we value our lives, I think we’re thinking mainly of these strings of actions and experiences our being alive allows us to participate in – which, being human, we are compelled to weave into a story.

One meaning of biological life is the suite of physical processes which the science of biology has discovered to be the source of the property of being alive. (Nearly) all living things are composed of cells. The chemical, electrical and mechanical processes that are going on at a molecular level within the cells constitute their biological life. Those processes carry out functions like growth, differentiation, metabolism and cell division. Similarly, tissues and organs carry out their functions to sustain the biological life of the organisms they compose. An organism is alive by virtue of these lower-level processes, and by carrying out its own life-sustaining functions.

Animating life plays no role in modern science or the scientific worldview, but it has a long and varied history in philosophy, religion and culture. Life in this sense is thought of as a force or ‘principle’ or spirit that is responsible for living things being alive. It animates them. It can be thought of as either individual or shared, and as personal or impersonal. Some believe in an impersonal life force that is present in all living things. But ‘anima’ is Latin for ‘soul’, and animating life can also be thought of as an individual life principle, entering the body of an animal or plant at the beginning of its (narrative) life, being the one constant through all its life changes, and then dissolving or leaving the body at death, perhaps (in the case of human beings) for a new destination. Such a soul-like animating life of a special human variety may be thought of as the essence of a person, bearing his or her personality. For animating life of the individual type, the beginning of life must be sudden – a new, discrete life principle is either present or it’s not – and in the case of humans that moment will constitute the beginning of a person, since the animating life/soul/personal essence will define that organism as a human being and as that person.

When pro-lifers talk of a baby being “a life”, or a person being a life, and when they speak of “human life” in that special tone (as if it’s a different kind of life from any other, which is not true of biological life, which is an ensemble of physical processes shared across species), I think they tend to have “animating life” in mind. Or perhaps they would say they mean by “a life” a unity of soul and body.

But I don’t hear much talk of soul. Personally, I suspect this was a conscious strategy by some Catholic intellectuals like Robert P. George who invented a way of speaking which was not overtly religious but was still theologically correct. This was necessary if anti-abortion legislation was not to be seen as based on religious dogma and so ruled out by the First Amendment. Not only did speaking of life instead of the soul produce the winning “pro-life” slogan (who wants to be anti-life, or pro-death?) but it had the added advantage (from an absolutist anti-abortion perspective) that the question of when the soul entered the body need never be raised. If you say ‘life’ instead of ‘soul’ then the question becomes simply “When does life begin?” And here’s the evil genius of the strategy: “When does life begin?”, if it is to settle a moral question, must be speaking of an animating life of the special, human kind that by its very presence constitutes a person. (Because murder is killing a person, not just ending some impersonal life.) But then pro-lifers can turn around and query biologists: “When does life begin? Oh, life begins at fertilization? Well then, science proves the fertilized egg is a person, and killing it is therefore murder.”

The problem, of course, is that the science of biology can only say when biological life begins. As a matter of fact, it doesn’t even do that, because biological life – the ensemble of physical processes that carry out vital functions – never actually begins from scratch (except in the distant past). It always just continues. You will find no biological research into “the moment when life begins” (fascinating as that sounds) because biological life never does. It just flows on. When an egg is fertilized a new organism is formed, with a new combination of genetic material (or, equivalently, the egg acquires new genetic material and is activated to develop into a new multicellular organism), but the same life (the same combination of physical processes) continues without a break.

Biology does not count lives. There is no scientific question of whether a many-celled organism has many lives or one. When a cell divides, whether the mother cell dies and two new lives are created, or one new life is created and one continues is not an empirical question. It’s just life. Biological life is a mass noun, like electricity, not a count noun. Your cell phone is not “an electricity”. Two phones are not two electricities. It’s the same electricity in both. By the same token, a baby is not “a (biological) life”. A baby is a living organism, and so is a zygote and so is an embryo. That’s not in dispute. But none of them are “lives” in the biological sense. That makes no sense. So when biology affirms that a fertilized egg is alive, that is not the same as saying that (an animating, personal) life begins at the moment of conception. That is not a scientific statement, and science does not “prove” that.

I know all this is a mouthful. As you might have guessed, I’ve been thinking about this topic for a long time. It has been frustrating, trying to discern and untangle the worldview assumptions that stand in the way of our understanding each other. I’ve tried my best to understand how pro-lifers can believe what they do, but it’s hard – though probably no harder than understanding how they can be Christians, or Trump supporters.

Dr. Mohler, as far as I can tell, doesn’t try to understand how rational people can disagree with him because he doesn’t believe that they do. He says,

“I will actually argue that virtually any woman who sees that ultrasound image does indeed get the obvious meaning that there is a baby, a baby developing in her womb. The extinguishing of that life is the extinguishing of the life of her baby. I don’t think a woman seeing an ultrasound image who goes ahead with an abortion is doing so after seeing the ultrasound unaware of what she’s doing, but rather that image has somehow been overcome by whatever rationale is behind the abortion itself.”

(Dr. Mohler says he “will actually argue”, but he mounts no argument. He speaks to no women. He provides no evidence. He merely asserts.) He calls Weigel’s article irrational and immoral, and accuses her of writing what she does simply to avoid a conclusion that is obvious to everyone:

“...if it is a baby and the obvious meaning of the ultrasound image is that there is human life in the womb, then there would have to be an entire moral shift in this country on the issue of abortion and that unborn life would have to be defended. So she writes that it’s simply an assumption, she says a wrong assumption, that an ultrasound image has an obvious meaning.”

Finally, he quotes Sean Davis:

“Like most treatises from abortion activists about how babies aren’t real people, Weigel’s comes across more as a sad attempt to convince herself than a credible attempt to convince her readers. No amount of euphemisms can obscure the truth that unborn babies are alive, that their hearts beat just as ours do, and that the abortion industry is dead set on killing as many of them as possible.”

The last statement in this quote is of course a stupid slander. It seems pro-lifers can be carried away by their “culture of death” rhetoric. Planned Parenthood seeks to, and does, reduce the number of unplanned pregnancies, thereby reducing the demand for abortions. As I said, I was not enthusiastic about Weigel’s article. Many of her arguments seem strained and unconvincing. However, Davis and Mohler are mistaken to believe that the facts that the unborn are alive and that their hearts beat just as ours do constitute strong arguments against abortion for people who do not already share their assumptions. As Weigel wrote, abortion opponents “act as if ultrasound images ‘prove’ that a fetus is equivalent to a ‘baby’.” They don’t.

Dr. Mohler concludes his podcast by saying,

“The culture of life must continue to make arguments on behalf of human dignity and the sanctity of human life. But, of course, in the public debate the culture of death has to make its arguments as well. We do well to look these arguments squarely in the face. In doing so, we’ll see the arguments as just as horrifying as we feared they were.”

I hope my readers do look my arguments squarely in the face, and reply to them if they would like. And I hope they will not find them horrifying, but instead that they offer a key to understanding how their neighbors can be pro-choice while being rational and without being murderous monsters. This honest difference of opinion has savagely torn our country apart for too long.

No comments:

Post a Comment